What is an ‘urban forest’?

‘Urban forest’ is a term that is being increasingly used by those engaged in thinking about (and even delivering) resilient cities. But what does it actually mean? There are various published definitions but for our purposes here we adopt a definition that we and our colleagues proposed last year:

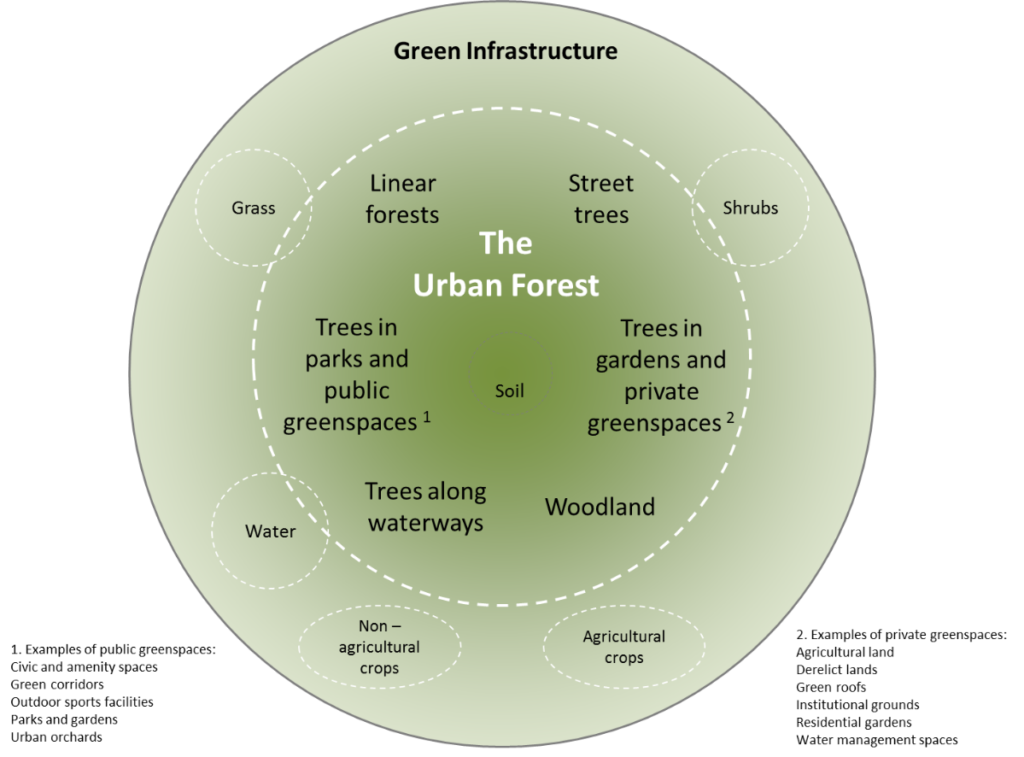

‘The urban forest comprises all the trees in the urban realm – in public and private spaces, along linear routes and waterways and in amenity areas. It contributes to green infrastructure and the wider urban ecosystem.’

(Introducing England’s Urban Forest; www.forestry.gov.uk/urbanforestry)

Figure 1: Illustration of our definition of the urban forest and its relationship to green infrastructure.

Like Green Infrastructure, the term urban forest is often used in generic and overly-simplistic ways. Our definition helps to illustrate that the urban forest is a component of the wider green infrastructure (Figure 1) and just as green infrastructure is comprised of various elements, so too is the urban forest. It is important to remember when discussing the urban forest that not all of its components deliver all of the benefits of urban trees. This fact is not well articulated in the current literature.

Components of the urban forest range from the ‘isolated tree’, to ‘lines of amenity trees’ like those found alongside roads or waterways, and ‘clusters of amenity trees’ such as those found in parks, to ‘urban woodland’. From this it is immediately apparent that the urban forest is diversely spread and that it is owned and managed by a wide array of individuals and institutions. Such a spread in ownership requires the strategic oversight of a city-wide urban forest management plan in order for trees to be used effectively in delivering resilient cities, and a need for this to work for private as well as public owners.

How do we enhance the benefits that the urban forest provides?

Some of the most important benefits that we get from urban trees are the interception of rainfall (which helps to reduce the risk of flash floods), the regulation of urban temperatures, and the removal of airborne pollutants. Others include improved physical and mental wellbeing from enhanced aesthetics and opportunities for recreation. Enhancing delivery of these ecological benefits, also known as ecosystem services, can be achieved through effective advocacy of an urban forest management plan – as demonstrated State-side (www.itreetools.org). Central to such a management plan is, typically, a call to increase canopy cover according to a ward-based assessment of deficiency.

Though increasing the presence of urban trees will, in theory, increase benefit delivery, it is a little more complicated than that. This is where our four urban forest components come in. In our new Forestry Commission Research Report (www.forestry.gov.uk/forestry/HCOU-4VXJ5B; bit.ly/fcrp026), we review the literature to show that single trees, for example, are particularly important in delivering the ‘shade provision’ ecosystem service. Lines of trees are useful in removing air pollutants. Clusters of trees are important in the delivery of the recreation ecosystem service, and urban woodlands are important components of an urban forest for reducing surface water flooding. The total amount of each of these components within an urban forest thus impacts the extent of delivery of these various ecosystem services. The profile of ecosystem service delivery will also differ between urban forests with different proportions of each of these components.

Tree species, size of the tree, the way it is managed, the location, its proximity to people and buildings, accessibility, and surrounding land cover are key indicators of the type and level of benefits that a particular component of an urban forest will provide. Our report also considers the delivery of ecosystem disservices and the trade-offs inherent in targeting the delivery of a particular ecosystem service.

So no, not all urban forests are equally beneficial. If we are to enhance the flow of urban tree benefits to society as a whole, the design and management of our urban forests must be considered. The long standing adage of ‘the right tree in the right place’ is reinforced by the findings of our report. Identifying the ‘right tree(s)’ and ‘right place(s)’ could be informed by an assessment of the current ecosystem services delivery and the opportunities to enrich our urban forests.

About the authors

Helen J. Davies

Centre for Environmental Sciences, University of Southampton

Dr Kieron J. Doick

Urban Forest Research Group, Forest Research

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute of Chartered Foresters.